History

Norwalk River Watershed AssociationThe History of Mills and Dams Along the Norwalk River

Arranged By Brent M. Colley. Histories of Mills and Dams coming from Wilbur F. Thompson articles written between 1915 and 1930, later made available by Irene Baldwin in 1965. Additional photos, maps and information to enhance the Thompson material were added in 2005.

The Old Stone Mill

by Wilbur F. Thompson.

John Taylor of Wilton was the first to operate a mill in the location that would come to be known as the Old Stone Mill, and at one time- Perry’s Glenburg Chemical Works. John Taylor’s Mill was called Taylor’s Woolen Mills or the Satinet Factory. He built a dam a short distance above the mill and a canal to convey the water to the mill (this canal is still visible from the train today). He also built the house by the mill and lived there many years.

Henry Williams, who lived a short distance below the mill, had charge of the dyeing, carding and spinning department; his wife was one of the weavers. A man named Eli Glover also worked there. He afterward ran the mills known as Glover’s Woolen Mill west of Sanford’s Station in West Redding (corner of Topstone Rd and Route 7 where Cains Hill is. Cains ran a Fulling Mill).

John Taylor was in business many years, and after he retired, a Welshman named Evans, from Derby, CT, continued the business. After this, Blackman Bros., from New Milford, ran it for a short time.

Later Dr. N. Perry, of Ridgefield, bought it; and fitting it up for a grist mill and to grind spices, called it the Glenburg Chemical Works. Perry attempted to change the name of Georgetown to Glenburg, but did not succeed. His son, Samuel Perry, had charge of the mill for many years. The famous remedies so well known in the 1850’s & 60’s were made here – composition powders for colds, magnesia powders for indigestion, the No. 9, a pain killer, demulcent, compounds for coughs, and many others. Spices were ground and all kinds of extracts were made and sold. The country stores all kept the Perry remedies, spices and extracts.

After the death of Samuel Perry, the formulas for the Perry remedies came into the possession of his brother-in-law, Eli Osborn, who made them for many years, at his home in Georgetown. The mill was sold to William J. Gilbert who leased it to different parties who ran it as a grist mill. Later the mill was owned by Samuel J. Miller…the roots of the G&B factory ran deep.

About Flax and Woolen Mills

Two of the most important products of the farms of long ago were wool and flax. On summer days flocks of sheep could be seen feeding on the hillsides and waving fields of blue-flowered flax could be seen on almost every farm.

Flax was not harvested the same as grain or hay, but was pulled up by the roots and stacked. Later in the season it was put through a process of sweating or rotting to separate the fibre from the woody part of the stalk. It was then crackled to break the wood or straw of the flax. This was done by beating it with wooden mallets. After this, it was hetcheled or hackled; this was done by drawing the stalks of flax over sharp pointed iron teeth thickly set in a block of wood. This separated the fiber from the woody or straw portion of the flax. The fiber, after hetcheling, was called tow or lint; this was cleaned and spun into linen yarn or thread, and woven on the hand looms into different kinds of linen cloth, and then bleached.

The wool was worked up in a different way. After being sheared from the sheep, it was washed and cleaned. Then it was carded into a light fleecy mass (like the cotton batting of today.) The hand cards were pieces of leather or thin wood thickly set with fine wire points which caught and separated the fiber of the wool. Sometimes the wool was bowed the same as hatters’ fur was in the olden times. This was done with a large bow strung with catgut; pulling the string caused it to vibrate in the wool, separating it the same as in carding.

After carding, the wool was formed into rolls, from which it was spun into woolen yarn or warp and then woven into woolen cloth of many kinds, and blankets. A cloth for dresses and skirts was woven, called linsey-woolsey. It had a linen warp and woolen filling; a heavier cloth made of the same materials was called fustian.

After washing, the cloth was dyed, fulled. and finished.; oftentimes the warp and filling were dyed before weaving. For many years all this work was done by hand on the farms where the wool and flax were raised. Later little shops and mills were built along the stream where the wool and flax were prepared. for weaving and where the home-made cloth was fulled and finished.

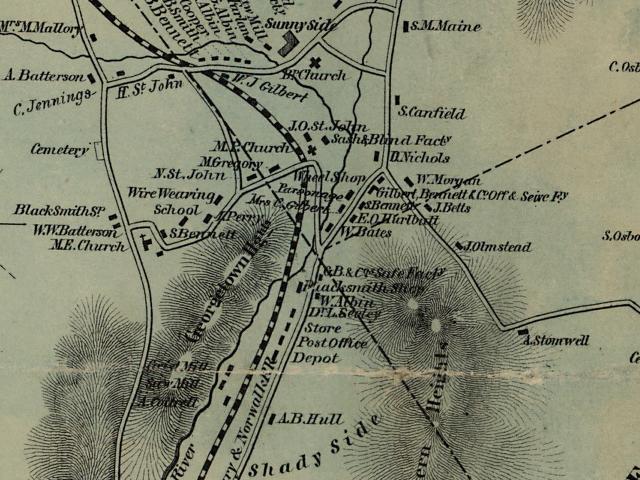

Mills Along Old Mill Road in Georgetown

by Wilbur F. Thompson & notes by Brent M. Colley.

From the early settlement of our state until about 1850, the people living in our rural communities were, to a great extent, independent of the outside world; the farms and little shops and mills producing almost everything used in the homes of their day. At one time there were approximately sixteen busy shops and mills along the banks of the Norwalk River from its source in Ridgefield to tidewater in Norwalk. Today all that remains are the bricks and stones of their foundations and dams. The information below (a large majority of which comes from Wilbur F. Thompson) explains their history and the individuals that worked them many years ago.

The first mill to be built in the early days was the Grist Mill, then the Saw Mill, Blacksmith Shop, Woolen Mill, Tannery and Cider Mill. Georgetown was no exception to the general rule, and along its streams and highways are found evidences of many little home industries that flourished, long years ago. It is probable that the first corn and grain raised in Georgetown was ground in the home-made mortars of wood or stone, with a pestle, or in the old Indian stone samp mortars which can be found in the rocks along the Norwalk River in many places.

The first Grist Mills where the early settlers of Georgetown had their corn and rye ground were located outside of the village. One stood on the west bank of the Saugatuck River, near the foot of Nobb’s Crook Hill. (This was about 1730). The miller’s name was Jabez Burr. Many years later a wind grist mill was built in what was called Dumping Hole or Hill (now in Cannondale School District,) about two miles southeast of Georgetown. Another Grist Mill located at the intersection of Florida Hill and Old Redding Road, operated by Peter Burr and dating to 1737 was a likely source for the settlers as well.

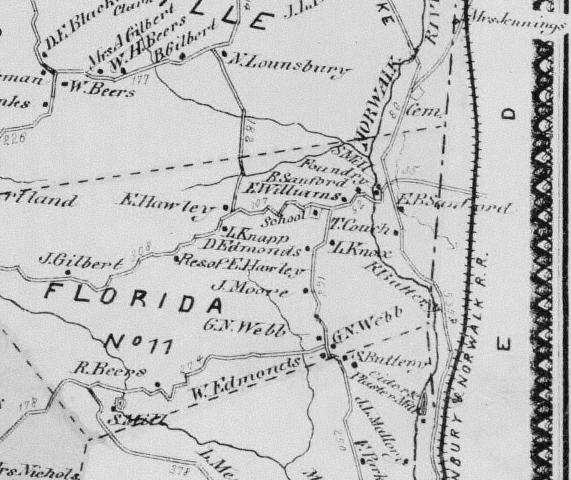

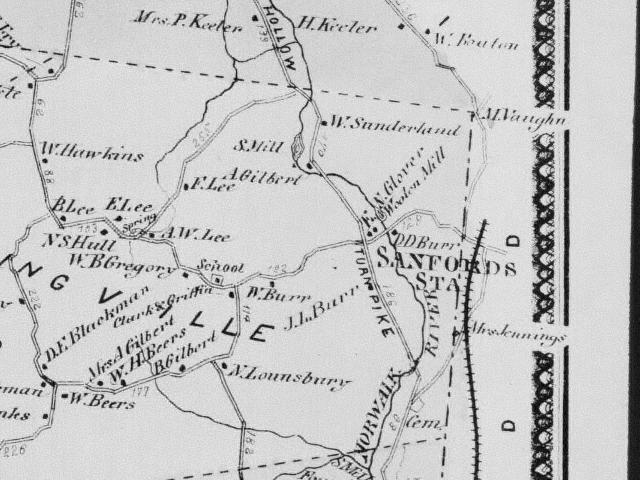

mentioned). The location is a tad to the left of E.B. Sanford between the “E” and “D”

The first grist mill in what is now the village of Georgetown was probably built and run by George Abbott. If there was one before this, the name of the owner is not known. In 1764 George Abbott, formerly of Salem, Westchester Co., Province of New York, bought of Ebenezer Slawson, of Norwalk, a mill privilege on the Norwalk River for the purpose of erecting a grist mill. The mill was built and he commenced to grind corn and grain. There is also a tradition that John Belden had built a saw mill on or near the same site, and Abbott purchased that mill site from him as well. Located on the only road between Danbury and Norwalk it was a very profitable business; people from miles around brought their grain to be ground, or logs to be sawed up into lumber.

Abbott ran the mills for many years and his wife (known as “Aunt Lucy”) kept a tavern or half-way house for the teamsters traveling the Danbury and Norwalk turnpike.

A long list of owners followed Abbott at this location.

- The next owner of the mill was Stephen Perry. He rebuilt the dam and mill; and it became known as Perry’s Mill.

- Later Joseph Goodsell the 1st. ran the mill.

- The next owner was Ephraim B. Godfrey and his son Wakeman Godfrey. Godfrey & Son ran the grist and saw mill for many years and did a large business. Glenburg Chemical Works would put Wakeman Godfrey out of business.

- Some time after, Edwin Gilbert bought the property, rebuilt the mill dam and mill, enlarging it, and fitting it up for other manufacturing; for a while, Betts & Northrop had a carpenter shop there as well. Blood’s patent flour sifter and other wire goods were made there at that time.

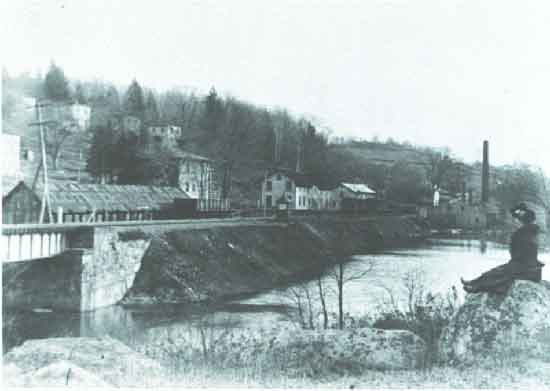

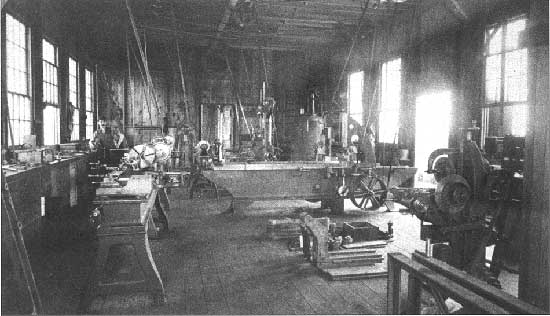

- Later the Gilbert & Bennett Co. gained ownership and changed it into a wire mill, the third floor of this mill was set up and ran the second machine in this country for making wire netting and fencing in 1869 and ’70. In 1865 Gilbert & Bennett & Co. had installed the first power machinery for making wire poultry netting. It was used for that line of work until it burned down around the early 1900’s. G&B converted this entire area into it’s “Lower Factory” wire mills.

The “Lower Factories” included several manufacturing buildings, a wire drawing plant and a dam large enough to create what was known as the Lower Factory Pond.

The Lower Factories were the last mills in this location serving Gilbert & Bennett well in their life span. G&B would later focus their attention on the factories we know today between North Main Street and Portland Avenue. Back then these factories were referred to as their Upper Factories. Improvements in the railroad, particularly the spur line that was run into the Upper Factories in 1874 led to the expansion of and focus on this location. The Lower Factories were all lost to fire over time.

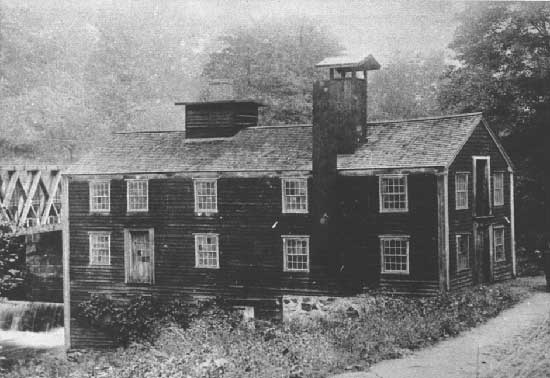

The Old Red Mill

by Wilbur F. Thompson and notes by Brent M. Colley.

Just above the Lower Factory Pond was the location of perhaps Gilbert & Bennett’s most famous mill, the Old Red Mill. The Old Red Mill was where G&B would come up with an innovation that was so versatile it would propel the company to greatness…Woven Wire. The list of woven wire applications and products is far too long to discuss in this document but I assure you it is one heck of an impressive list.

An abbreviated history of this mills at this location is as follows:

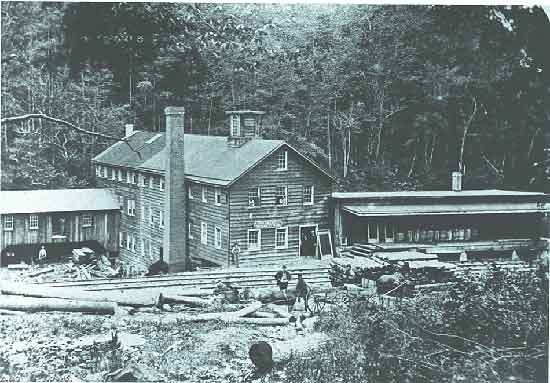

Some years after the War of the Revolution closed, David Coley of Kettle Creek, Fairfield (now Weston) moved to Georgetown. Coley was an iron worker who bought a mill site in the same location as what would become the Old Red Mill on the Norwalk River; he built a dam and shop, put in a wooden water shed, a furnace for smelting iron ore, a trip hammer, and commenced bus-iness. Many kinds of iron goods were made, ploughshare points, shovels and irons, cranes, pots and kettles, and ovens. This industry gave work to quite a number of men and continued for many years until Coley gave up the business and the shop was left vacant. Later it was burned.

In 1821 Winslow and Booth ran a comb factory on Coley’s iron works site, erecting a small shop. This business continued for some time and gave employment to quite a number of people as well. Cheaper grades of combs were made of cattle horns. The finer grades of women’s side and back combs were made of tortoise shell. They like Coley gave up their business and moved away.

In 1834 the Gilbert & Bennett Co. bought the mill site, rebuilt the mill dam and built the shop long afterward known as the Old Red Mill. A wooden water wheel was built to furnish power. The mill had two stories and a basement. The top floors used for curled hair production, the basement was where the sieve rims were steamed and bent into shape.

the machines and were powered by the water wheel.

In 1836 G&B experimented with drawn wire in an attempt to improve upon the woven horse hair products they were selling at this time. The experiment was a success and they quickly began furnishing the Old Red Mill and Old Red Shop with modified carpet looms to produce their “wire cloth”. The production of cheese and meat safes soon followed. Following the introduction of hard coal for fuel, a coal ash sifter or riddle was invented. Later woven wire ox muzzles entered the product line, then they discovered glue dried very well on woven wire and came off much easier than the cotton cloth in use at the time. The product line grew year by year until they came up with the ultimate application…insect screens or as we call them today window screens. The insect screen was an instant hit on the market, cheesecloth was in use prior to this so you can imagine the improvement it made.

The Lower Factories mentioned earlier in this document came into play soon after. By the 1860’s sieve production along with other branches were moved into other shops and the Old Red Mill was used for drawing fine wire and later for tinning and galvanizing wire.

Gilbert & Bennett

The history of mills and dams is not complete without information on the Gilbert & Bennett Manufacturing Company as G&B exemplifies the flourishing 19th century mill.

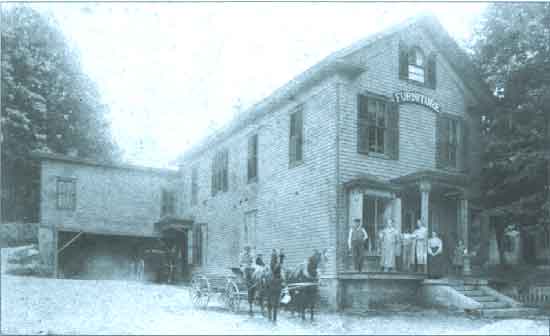

In 1827, the Red Shop became the first mill occupied by the company and as business prospered was later purchased. The Red Shop stood on the corner of Rt. 57 and Old Mill Road. As the business grew improvements were made to the shop for efficiency: a three-story addition was built, A mill dam was built across the brook, and a small pond was formed about 100 feet long and 60 feet wide. This supply pond, or reservoir, located on what is now Sasqua Trial, off Covenant Lane. On the north side of the pond was the road to Weston, lined with rows of willow trees. On the north shore of the reservoir were vats for cleaning, washing and sorting the hog, horse and cattle hair used in the curled hair industry; there were also platforms for drying the hair. Later this work was done in the rear of the shop.

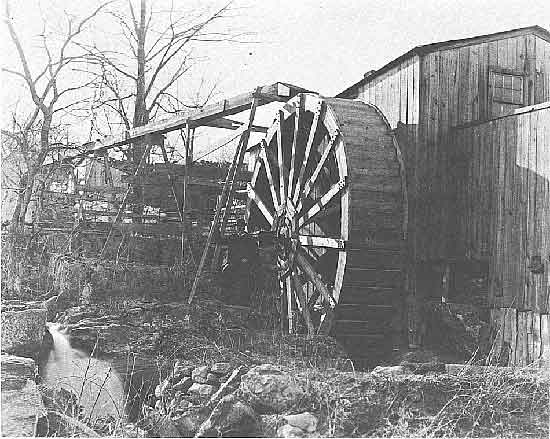

The first story of the shop was used for sieve making, and the second for the curled hair business. On the floor was a hairpicking machine and two hair rope twisters. The power was furnished by a wooden overshot water wheel (this was outside the shop on the north side.) The water was carried in a wooden flume from the pond onto the top of the wheel. The gate in the reservoir was opened every morning and shut down at night.

After the horse and cattle hair was cleaned it was twisted into ropes, then boiled to set the curl. After drying, it was wound into hanks or bundles, and sold in this form or picked out by hand ready for use in cushions, etc. The longer horse hair was picked and kept separate and woven into bottoms for the hair cloth flour and gravy sieves. This was woven on small frames called looms, into squares a little larger than the sieves they were to cover. This weaving was done by women of the village. First by the women in the families of the firm, and later by Mrs. Polly Canfield, Mrs. Ezra Brown, Mrs. Sherman Bennett, Mrs. Matthew Bennett and her daughters (one daughter, Mrs. Waterman Bates, was one of the last ones to weave haircloth in Georgetown).

In making the sieves, the thin wooden rims were cut from whitewood plank sawed from logs at Timothy Wakeman’s saw mill that stood north of where the upper Gilbert & Bennett Mfg. Co.’s plant now stands, then smoothed by hand, steamed and bent into shape and nailed; the hair cloth bottom was then put on and held in place by a narrow hoop or rim, which was fastened on by nailing. The edges of the haircloth were then bound around the sieves with waxed thread. This work was done by women at their homes – it was called binding sieves. Mrs. Aaron Bennett, Mrs. Samuel Main, Mrs. Aaron Osborn, Mrs. Samuel Canfield, Mrs. Burr Bennett, Mrs. Orace Smith and others did this work.

The men who worked to the curled hair and sieve industry at different periods in the Red Shop were Benjamin Gilbert and his sons William J. and. Edwin; Edmund O. Hurlbutt, John F. Hurlbutt, William B. Hurlbutt, Aaron Bennett, Sturges Bennett, Isaac Weed (Mr. Weed married Angeline, daughter of Benjamin Gilbert, and built the house opposite the Sturges Bennett place,) Samuel Main, Aaron Osborn.

All this time, the weaving processes were being accomplished by hand, and the material used was horsehair. Horsehair was at the best, unsatisfactory-which caused the company to ask itself: “why could not some other material, more durable, more efficient, be substituted?” And not stopping at merely thinking it, they purchased some fine wire and began to experiment. The commercial weaving of wire by hand was impractical and machinery for such a purpose being unheard of, they improvised and borrowed a neighbor’s carpet loom and so the first wire cloth came into being.

In 1834 the Gilbert & Bennet Co. found that the growing business needed more power than the little mill pond furnished and bought the mill site of Winslow and Booth on the Norwalk River. Winslow and Booth ran a comb factory there making combs from cattle horns and tortoise shells in the 1820’s. Prior to Winslow and Booth, the mill site was owned by David Coley, an iron worker; he built a dam and shop, installed a wooden water shed, a furnace for smelting iron ore, a trip hammer, and commenced business. Some of the ore was brought from Roxbury and Brookfield and some was taken from the ledge east of where Jessie Burr Fillow lived, on the road from Branchville to Boston district. There is a tradition that there was an iron furnace near this ledge before the War of the Revolution. The limestone used in smelting the ore came from Umpawaug hill. Many kinds of iron goods were made, ploughshare points, shovels and irons, cranes, pots and kettles, and ovens.

G&B rebuilt the mill dam and built the shop long afterward known as the Red Mill. The mill had two stories and a basement. The first floor was used for the curled hair industry using power. In the basement the sieve rims were steamed, bent into shape, and later other work was done there as well. A wooden water wheel was built to furnish power for the mill.

With the weaving of wire cloth, the process of making of cheese and meat safes commenced. Aaron Osborn did this work, assisted by his brother, Eli Osborn. Aaron Osborn created these cheese safes for nearly fifty years. With the introduction of hard coal for fuel, the coal ash sifter or coal riddle was made. Samuel Bennett, Henry Williams and others worked at this branch. Later ox muzzles made from wire were introduced. Most of the men who worked in the Red Mill had worked in the Old Red Shop doing the same kind of work.

On Oct. 15, 1835, Benjamin Gilbert deeded to Sturges Bennett and William J. Gilbert each a one-third interest in the Red Shop, the land (1/4 of an acre) with the mill pond, also rights in the reservoir on the hill. Near the Red Shop on this land was a small two-story building used by Uncle David Nichols as a wagon shop (part of this building was used by Benjamin Gilbert be-fore the Red Shop was built.) The price paid was $133 for each third. The land was bounded on the north, east and west by the highways, on the south by Sturges Bennett’s home lot.

In 1836, it was found the light cloth and carpet looms in the village were not heavy enough for wire weaving. A few looms were built and set up on the third floor of the Red Shop. Among those who wove wire cloth at this time were Isaac C. Perry, George Perry, Moses Hubbell and his wife Betsy, William Perry, and probably others. William Perry wove a fine wire cloth, called strainer cloth, used for straining milk and other liquids. George Perry built a shop south of his home which was later owned by John Hohman, and wove for the Gilbert & Bennett Co. Isaac Perry’s son-in-law also built a shop for weaving.

James Byington, Aaron Jelliff, Henry Olmstead and his brother William, Lorenzo Jones, Thomas Pryor, George Gould, Anton Stommell, George Hubbell, and Granville Perry wove wire cloth in the old Red Shop. As the business grew, Anson B. Hull was hired as Bookkeeper. The office was on the first floor of the shop; in connection with book-keeping, he ran a small store. He was with the company for many years. Later he moved to Danbury, where he was freight agent for the D. & N. R.R., until his death.

In 1842 Edwin Gilbert became a member of the Gilbert & Bennett Co. (40 years later he became president of the Gilbert & Bennett Mfg. Co. ) He, with his brother William J. Gilbert and E.O. Hurlbutt, comprised the selling force. Their selling methods being to load Conestoga wagons and deliver through the country as sales were made. Even under these difficult conditions, the sale of Gilbert & Bennett goods spread throughout the South and as far West as the Western reserve of Ohio.

In 1847, Benjamin Gilbert, the founder of the business, died after an illness of several years that incapacitated him from active business. A saw mill was established for making sieve frames in 1848 and in that same year, steam power was first introduced as a source of power. Because of Gilbert and Bennett’s rather isolated location, it derived its power not from coal but from water turbines. Water pressure became a constant with the purchase and control of Great Pond, a reservoir located 5.27 miles northwest of the mill on the Norwalk River at the Ridgefield-Redding town line in that same year.

The business at the time was still based on sieves and curled hair. Additional space could not go to waste, so in the year 1850, the manufacture of glue was added to further expand the company. The existing glue manufacturing process was studied by the company and found to have several disadvantages. They found that because glue was being dried on cotton netting some of it adhered to the fabric, this was a waste and led to higher costs. Another disadvantage was that the glue itself would contain bits of cotton which interfered with its adhesive quality. They resolved these problems by manufacturing wire netting upon which the glue would be dried. When the glue dried, it could be separated from the wire netting with little difficulty, and as a result revolutionized the glue-drying process across America.

In 1853 David H. Miller of New York City entered the employ of the Gilbert & Bennett Co. as bookkeeper. He brought in fresh ideas and new ways of working which greatly increased the efficiency of the company. (Fifty-three years later he became president of the Gilbert & Bennet Mfg. Co., and held that position until the time of his death in 1915). The Rapid growth of the Gilbert & Bennett Co. continued with Edwin Gilbert as salesman and Charles Olmstead running one of the freight wagons. With the building of the D. & N. R. R., the freight wagons were taken off one after another and the railroad did all the carrying of goods. One of these old freight wagons was used as late as 1864 carting materials between the factory and the depot. Edmund O. Hurlbutt withdrew from the firm in 1860.

With the building of other factories, one by one, the various branches of the industry were moved from the old Red Shop, until only the wire weaving was left. In 1861, Eli G. Bennett opened a dry-goods and grocery store on the first floor of the Red Shop. The business grew until the whole floor was occupied, and a large amount of business was done. Here many young men received their first business training. In 1869 Sturges Bennett who now owning the property had the Old Red Shop torn down and built in its place the store known for many years as Connery’s store. The timbers of the Old Red Shop were bought by Anton Stommell, who used them in building his house on the street running east from the Weston road, which is now Highland Avenue. Later he sold it to Elijah Gregory.

The Red Mill was phased out in this time period as well, and was used strictly for the drawing of fine wire, tinning and galvanizing wire in it’s later years. In 1889 the Old Red Mill was burned down and new mill was built in its place.

A wire mill was built on the factory premises in 1863 to provide “facilities for drawing iron wire.” Prior to this, the manufacturer had purchased iron wire from a mill in Worcester, Massachusetts. Distribution was becoming more accessible, the tools of commerce in the shape of rail and water shipping and transportation facilities were rapidly extending their scope. The telegraph was shortening the distance between manufacturer and purchaser. Wholesalers were tightening the link between making goods and selling them. So, expanding as rapidly as their needs justified, Gilbert & Bennett & Co. added new buildings and equipment, in 1865 installing the first power machinery ever used in the United States for making wire poultry netting. For many years they manufactured all the poultry netting made in the United States. This was not a large amount at the time, for the manufacturing was but a small part of the transaction as the trade had to be educated to its use. Gilbert & Bennett with perfect confidence in their goods continued to push them and the limited field at the time expanded to cover every part of the United States.

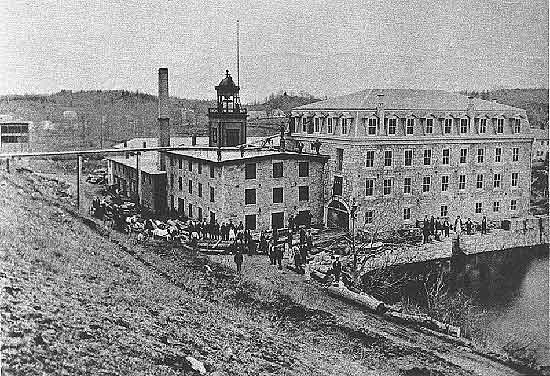

A fire destroyed the plant on Sunday May 11, 1874. Just at the sun rising, the cry of “fire” startled the village, and the latest, most complete and most valuable of the factory buildings was found to be on fire. There was no fire apparatus with which to fight the flames, and the company’s officials and the throngs of men, women and children that quickly gathered could do nothing but look on while building after building with its intricate and costly machinery was reduced to ashes. In an hour and twenty minutes the buildings were destroyed. Damage amounted to $200,000 for which the mill had $40,000 of insurance. The decisions that were made in rebuilding the properties insured Gilbert and Bennett’s success for generations to come. One of those decisions was to lobby the Danbury and Norwalk Railroad to run a line into the mill. The Danbury and Norwalk Railroad traveled through Georgetown as early as 1852, but it was during the 1874 reconstruction that the railroad was convinced to run a spur line into the mill property. The track that came into the mill, branched off from the railway just before the Georgetown Train Station where Miller Hall stood, two team tracks split to the left, one lead to the back of Georgetown Station and the other extended further to the road. The main track split in two, where it joining again in the factory. In addition to Miller’s Hall, two small sheds also stood, one of which was a coal shed. The spur line enabled the company to ship and receive material more efficiently, and reduce the manpower required in the process.

The new railroad spur line had another advantage: Steam power. Steam power was dependent upon coal and coal was a raw material transported in bulk by rail. Steam power added a great degree of flexibility to the modern manufacturer. The mill owner was no longer a slave to a specific location on a river, nor was he at the mercy of seasonal variations in the amount of water available in an out-of-the-way stream allowing him to make consistent schedules for production. Gilbert and Bennett was no longer dependent on the Norwalk River.

Following the fire G&B made another successful decision: The Iincorporation of The Company. Gilbert and Bennett was reorganized as a joint stock company on May 30, 1874 and the machinery that adorned the new buildings was the newest and best possible. The mill was opened and operating within the year.

The officers of the corporation were: Sturges Bennett, President; William W. Beers, Treasurer; David H. Miller, Secretary

The above officers, with Edwin Gilbert and William J. Gilbert, comprised the board of directors. William W. Beers was later made president of the company, serving in that capacity from 1876 until his death in 1879. The newly incorporated company went into the field with a vigor which within a few years multiplied their sales and output many times over.

About this time steel replaced the iron wire of earlier days. The increased facilities of the wire mills enabled the company to handle the steel and to draw all such wire used in their manufacture. This they continued into the 1980’s, using a specially selected stock of the highest grade. Bronze, copper, and brass wire were drawn for use in their goods as well. Gilbert & Bennett was the first in the country to manufacture and market galvanized wire cloth. This soon replaced the plain iron wire cloth which until that time had been carried in stock by all hardware dealers.

By 1887, the wire industry had finally come of age and the increase of business taxed their factory capacities to the point that the glue and curled hair departments had to be sold off. From that point forward, the factory was devoted to wire fabrics exclusively.

Gilbert and Bennett continue to prosper at the turn of the century attracting not only new business but immigrant labor as well. Swedish immigrants actively recruited by the company arrived in great numbers by the end of the 19th century. The Swedish neighborhood was first located in the Weston section. By the 20th century they occupied a good portion of the housing provided on Portland Avenue by the company, where they built their church. Scandinavian surnames also predominated on New Street by 1927. Ethnic neighborhoods were also established by the Polish and Italian immigrants in Georgetown, although a few Italian Americans lived in the Wilton section of Portland Avenue and in Ridgefield section of Branchville.

In the 20th century the company’s reliance on the Norwalk River dimished but it’s association with it did not. Great Pond, no longer a source of power became a source of entertainment. The pond purchased in 1848 was used for family gatherings by the employees of the factory: swimming, fishing and sunning in the summer, skating in the winter. My grandfather recalls walking and/or hitching rides to the pond throughout his childhood. When a trip to Ridgefield was out of the question the factory’s “Upper Pond” off of Portland Avenue was a popular swimming hole and was used by the Town of Redding’s in the 1960’s thru the early 70’s when Topstone Park was established. The swimming area at the “Upper Pond” was created and maintained by the Georgetown Lions Club and the local Boy Scout Troop who aided in the removal of gargage each spring. Among the clutter picked out of the pond in April of 1967 according to the Redding Pilot were a television set, a baby carriage, and over 60 tires. The Lower Factory Pond was never used for swimming or fishing as it was heavily polluted by the factory’s wire manufacturering waste. My grandfather noted that “it glowed green” at one point in his childhood.

The Great Pond, Upper Factory Pond and Lower Factory Pond were all washed out in the “Flood of 1955”. Practically all of the dams on the Norwalk River were destroyed by the flood. The dam at Buttery’s Mill on the Silvermine River, suffered extensive damage as well.

Today Great Pond continues to serve the community as a swimming hole. The Gilbert and Bennett Company transferred it’s rights to the Town of Ridgefield in the 1990’s. The Upper Pond in Georgetown remains a popular fishing hole for local residents and their children and some even venture out in a small boat from time to time.

Ridgefield Mills along the Norwalk River

At this time I have limited information on the mills above Georgetown/Redding in Ridgefield. However, the map below shows Eli Glover’s Woolen Mill mentioned above in the Old Stone Mill text and a Saw Mill above it in the location of the Golf-Art Building located there today. In addition to Glover’s Woolen Mill there was also a Fulling Mill owned by a man named Cain…thus Cains Hill Road above it.

What Powered These Early Mills?

Answer: The Water Wheel. The function of a water wheel is to power a machine to perform a task. Although we don’t think of it with today’s advanced computers and production systems, the water wheel was one of this country’s first labor-saving devices. The amount of power or energy generated by the wheel is measured and described in horsepower. A unit of horsepower is equivalent to 550 feet power per second. Water wheels of the 19th century could operate at ten to thirty horsepower but most functioned with between fifteen and twenty. Water wheels were made of wood. For best results they should be kept in constant use. If not, parts would dry and shrink, eventually becoming loose. Northern mill owners often would build wheels into mills—devising crude heating systems to keep it ice-free in winters. Buckets, into which the water was directed, would leak, diminishing the amount of power of the wheel. The wheel was certainly not indestructible under the best of conditions. Over a span of five to ten years, most parts of the wheel would need to be repaired or replaced.

The wheel was set in motion by water entering its buckets. The flow of water was the most crucial contribution of the entire process. To insure a constant flow, a dam was built as close to the mill site, and wheel, as possible. If the dam was any distance from the wheel, water had to be carried from the dam to the wheel via a canal or flume.

Efficiency of all wheels depended upon the head (the difference in level between water feeding the wheel and that leaving it.) A wheel performing at a site with a great head water would be quite large and use many buckets. For best results, water should leave the wheel quickly. Construction of tailraces were used for this purpose. Tailraces were made of oak, pine, or cypress as these woods would contribute most to a long existence.

Mills of the 19th century generally used three types of wheels. The overshot wheel was one that water entered from the top. Its diameter could be as great as sixty feet and its width could be three feet. Buckets were ten to fifteen inches in depth and the head for efficient operation was ten to forty fest. It operated at approximately 65% to 75% efficiency.

The breast wheel allowed water to enter at the side just above the shaft. It operated best with an eight to ten foot head and the efficiency level for the breast wheel was 50% to 60%. The undershot wheel was commonly found at medium-sized dams of five to eight feet. It functioned with a low head and the bottom of the wheel was always submerged in the stream. A gate was installed at the bottom of the dam to direct a constant flow at the wheel’s vanes. (The undershot had no buckets as there was no need to hold the water for any length of time). The vanes were placed eighteen to twenty-four inches apart. This wheel could operate when water in its reservoir was very low, but at best operated only at 40% efficiency.

Why the demise of these once active mills?

The year 1860 saw “sixteen busy shops” along the Norwalk River from its source in Ridgefield to the Norwalk town line. By 1923 there were four or five. Mills along the Norwalk River in Wilton and Redding as well as those in Weston collapsed for the very reasons that factories in Norwalk, Danbury, and Bridgeport prospered. These small mills were dependent on water for their source of power. They didn’t move to steam because they weren’t located on major rail lines where coal could be readily imported (*with the exception of Gilbert and Bennett). Also, most mills were not large enough for this type of major transformation. The largest mill in Wilton in 1860 manufactured shirts. It employed twenty-four people. The small mills of Fairfield County couldn’t compete with factories in larger cities which manufactured their product faster and cheaper, if not better than they could. The small, interior mill town that could not attract a railroad not only suffered from access to raw materials. It also was at a disadvantage transporting its products to markets. But the ultimate death knell for the water-powered mill was the sophisticated marketing practices that larger manufacturers and their profits could afford. Big companies opened retail stores to sell directly to their customers. Catalogue buying allowed shoppers to conduct their business through the mail, eliminating the need for peddlers. And advertising in newspapers signified that 19th century manufacturing had become a multi-faceted, big business. Weston, Wilton, and Redding mills were in a struggle to survive, and they were in way over their heads.

Yet Georgetown’s wire mill, Gilbert and Bennett, not only survived but prospered. It succeeded because its management made the same necessary decisions that leaders of all successful American industries were making. In Gilbert and Bennett’s case, these were the same steps they had been taking since its establishment in 1818. The Georgetown mill continued to adapt to changing markets and economic conditions and they wisely foresaw future trends and developments. Gilbert and Bennett also benefitted from a vast amount of good fortune and very loyal, innovative employees.

As mentioned earlier, growing 19th century factories moved to steam power. Because of Gilbert and Bennett’s rather isolated location, it derived its power not from coal but from water turbines. However, G&B’s isolation problem was solved in 1874 when the railroad was convinced to run a spur line into the mill property and steam power soon followed.

Another key to developing urban centers of manufacturing after the Civil War was immigration. Before 1850 immigrants were outwardly deterred from settling in Connecticut by property ownership restrictions. By the 1870s and 1880s, however, foreigners were seen as a cheap and abundant source of labor. Immigrants were drawn to large cities because many were ports or located on important transportation lines. Once there, unskilled factory jobs, usually in areas in or within walking distance of their neighborhoods, provided the necessary employment and security. Although harassed by the Know-Nothing Party members in the 1850s, and again in the 1880s and 1890s by the American Protective Association, and inspite of main-line Democrat and Republican conservative, anti-labor, anti-immigrant attitudes, immigrants were here to stay. In 1890 Connecticut had a rural population of 123,097 and an urban population of 623,161. And by 1900 foreign-born residents made up 59% of the state’s people.

Visit www.historyofredding.com for more information on the History of Redding and Georgetown, CT.

To read about the massively destructive Norwalk River flood of 1955, click here.

Click here to return to the top of page